The gang discusses two papers that look at the fossil record of fishes. The first paper looks at the ontogeny of ancient lampreys, and the second paper investigates the impact genome duplication had on the evolutionary history of teleost fishes. Meanwhile, James finds a gnome, Curt has an adorable ghost problem, Amanda appreciates good music, and we are all back on our b#ll$h!t.

Up-Goer Five (Curt Edition):

Our friends talk about two papers that look at animals that live in the water and have hard parts on the inside. The first paper looks at some of these animals which have a round mouth. These animals today are very different as kids then as grown ups. As kids they live in the ground and pull food out of the water. As grown ups they move through the water and eat other animals. This paper looks at old parts of these animals from a long time ago to see if the kids always did this. They find that these very old animals did not have kids and grown ups acting so different. This means that having the kids do something different is a thing that is new, even though people have thought that these animals have always done this.

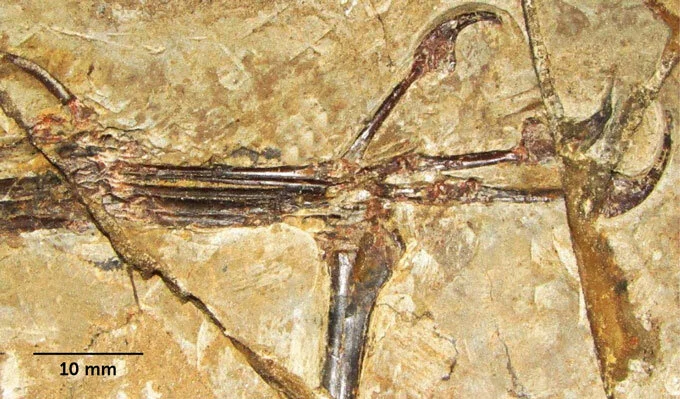

The second paper looks at the how animals with hard parts that move through the water had the bits inside them that store how to build them get a times two. When there are more bits that store how to build them, it makes the homes in the hard parts bigger. So you can use how big these homes are in the hard parts to learn something about how many bits these animals have. Using old hard parts from old animals and a tree that shows which of the animals are close brothers and sisters to each other, they look at when changes in how big these homes in the hard parts were in the past. And since how big these homes are tells us how many bits that store how to build them they have, we can also see how these bits are changing through time. People have thought that getting more of these bits may be why there are so many of these types of animals. This paper shows that it may not be that simple. The number of bits goes up first, but the number of new animals does not go up at that time. Instead, it happens after big changes in the world. It is possible that these bits may have helped in bringing the number of these animals up, but it alone does not explain it.

References:

Miyashita, Tetsuto, et al. "Non-ammocoete larvae of Palaeozoic stem lampreys." Nature 591.7850 (2021): 408-412.

Davesne, Donald, et al. "Fossilized cell structures identify an ancient origin for the teleost whole-genome duplication." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118.30 (2021).